Susceptibility and Tolerance

Herbicide susceptibility is the degree to which a plant is subject to injury or death due to a particular herbicide. Herbicide tolerance is the inherited ability of a species to survive and reproduce following herbicide treatment. There was no selection to make the plants tolerant; those plants simply possess a natural tolerance.

Consider the following example to distinguish tolerance and susceptibility:

Fall panicum

Common cocklebur

Clethodim will severely injure or kill fall panicum. Fall panicum is thus said to be susceptible to clethodim. On the other hand, clethodim has no activity on cocklebur. It has never controlled this weed, and cocklebur is said to be tolerant of clethodim.

Weed Population Shift versus Herbicide Resistance

(Content courtesy Dr. Alan York, NCSU)

A weed population shift is a change over time in the relative abundance of the species comprising a weed population. With the repeated use of an herbicide, certain species may become dominant due to selection for those that are tolerant. In some cases, weed shifts can also occur when a ‘low’ rate is used repeatedly, and more difficult to control species may become dominant. These populations are not herbicide-resistant.

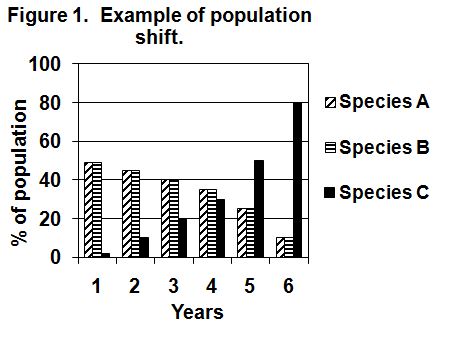

Figure 1. Species A and Species B are susceptible to a particular herbicide while Species C is tolerant of that herbicide.

In the hypothetical example in Figure 1, Species A and Species B are susceptible to a particular herbicide while Species C is tolerant of that herbicide. Species A and Species B each originally comprise 49% of the population while Species C makes up only 2% of the population. With repeated use of that particular herbicide, the percentage of the population comprised of Species A and Species B decreases over time (because the herbicide controls those species, hence they do not reproduce) while Species C makes up a greater percentage of the population (because the herbicide does not control Species C and that species continues to reproduce).

Three examples out of the many weed population shifts that have occurred include the following:

- Shift from crabgrass to fall panicum after intensive atrazine use

- Shift from fall panicum to broadleaf signalgrass after intensive alachlor use

- A buildup of morning glory and dayflower species after intensive use of glyphosate

Herbicide resistance causes changes in the composition of the population because of resistant biotypes. Originally at very low frequencies in the weed population, resistant biotypes build-up when the herbicide to which those individuals are resistant is used repeatedly.

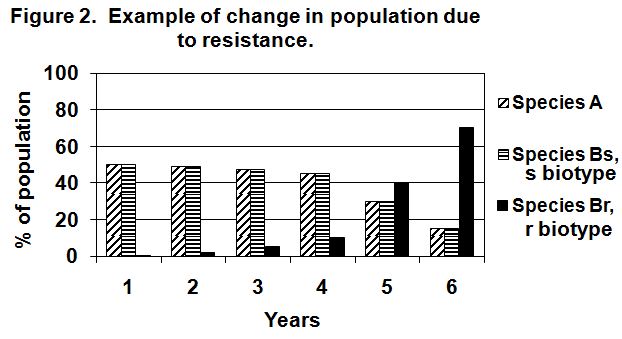

Figure 2. Example of a change in the composition of the weed population due to resistance.

Figure 2 shows a hypothetical example of a change in the composition of the weed population due to resistance. Except for a very low frequency of Species Br (biotype resistant to herbicide X), the population consisted almost entirely of Species A and Species Bs (biotype susceptible to herbicide X). If herbicide X is used extensively, the percentage of the population comprised of Species A and Species Bs decreases over time while the percentage of the population made up of Species Br increases.

Selection and selection pressure

Selection is the process by which control measures favor resistant biotypes over susceptible biotypes (see Understanding Resistance). Selection pressure refers to the intensity of the selection.

Mode of action and target site or mechanism of action

Mode of action (MOA) describes the plant processes affected by the herbicide or the entire sequence of events that results in the death of susceptible plants. It includes absorption, translocation, metabolism, and interaction at the site of action. The target site of action or mechanism of action is the exact location of inhibition, such as interfering with the activity of an enzyme within a metabolic pathway.

Herbicides are organized by families that share a common chemical structure and express similar herbicidal activity on plants. Of the hundreds of different herbicides on the market today, many of them work in exactly the same way or, in other words, have the same mechanism of action. Fewer than 30 plant-growth mechanisms are affected by current herbicides.

Types of resistance

Multiple resistance is the phenomenon in which a weed is resistant to two or more herbicides having different mechanisms of action. An example would be a weed resistant to sulfonylurea herbicides (WSSA Group 2 herbicides, ALS inhibitors) and glycines (WSSA Group 9 herbicides, EPSP synthase inhibitors). Multiple resistance can happen if a herbicide is used until a weed population displays resistance and then another herbicide is used repeatedly (without proper resistance management) and the same weed population also becomes resistant to the second herbicide, and so on. Multiple resistance can also occur through the transfer of pollen (cross-pollination) between sexually compatible individuals that are carrying different resistant genes.

Cross-resistance occurs when the genetic trait that made the weed population resistant to one herbicide also makes it resistant to other herbicides with the same mechanism of action. An example would be a weed resistant to imidazolinone herbicides (WSSA Group 2, ALS inhibitors) and sulfonylurea herbicides (also WSSA Group 2, ALS inhibitors). Cross-resistance is more common than multiple resistance, but multiple resistance is a potentially, greater concern because it reduces the number of herbicides that can be used to control the weed in question.

Compiled by Dr. Wayne Buhler, PhD