Honey bees live and function together as an intricate insect society. Each colony consists of 3 kinds (or castes) of individuals. At the heart of the honey bee colony is the queen, which can lay up to 2,000 eggs per day and lives for 2-4 years. Colony duties are carried out by sterile female worker bees, which live for an average of four weeks during the summer and much longer during the winter. Several hundred male drones live during the summer months and serve only for reproductive purposes.

The number of bees in a colony varies by the season and the availability of nectar and pollen-bearing blooms. Their numbers may drop from a peak of up to 60,000 bees in midsummer to only 8,000 or fewer after a long winter. The vast majority (98-99%) of the bees in a colony are the workers that carry out specialized tasks based on their age:

House bees:

House bees:

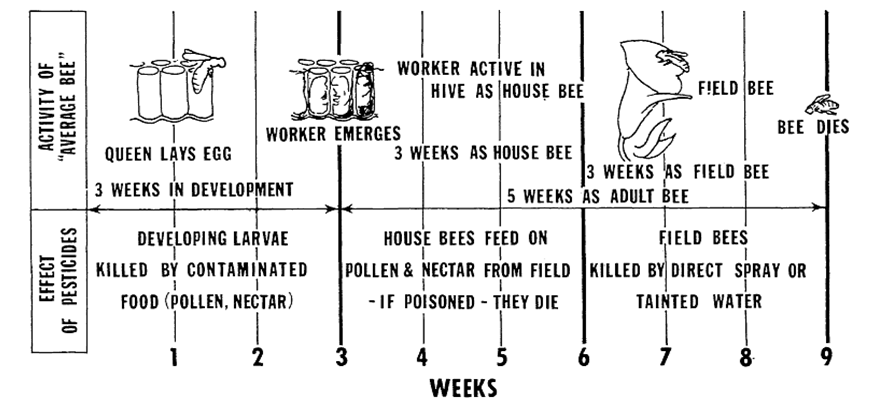

These bees are the youngest worker-adults, up to 21 days old. They care for the brood (eggs, larvae, and pupae), process the food, and clean the nest. House bees can be poisoned by contaminated pollen, which is collected and brought to the hive by field bees, then stored in the hive.

Field bees:

These bees are workers 21 days old and up. They are capable of amazing feats, such as communicating exact locations of nectar sources to their nestmates by orienting to polarized light and the sun, ventilating and air conditioning their home, and defending their family with their very lives. Field bees can be killed by contact with pesticides outside the hive, but most of the time they collect contaminated nectar and pollen and contribute to poisoning their nestmates. If field bees are killed, then young bees are forced into the field earlier than normal, further stressing the colony.

Worker bees:

Worker bees:

Worker bees can forage 2-3 miles from their hives and may visit multiple plant species in both crop and non-crop areas for nectar and pollen throughout the growing season. The time and intensity of pollinator visitation to a crop or vegetated area depend on the abundance and attractiveness of the bloom. The flowers on some crop plants may be open to honey bees all day, while others are only attractive in the morning or early afternoon. Once a nectar source is found, bees prefer to work that particular plant or crop to exhaustion before changing to another plant (see Malcolm Sanford note below**). The daily activity of bees is also important to keep in mind for timing certain pesticide applications: unless it is raining or below 55 degrees F, bees forage from sunup to sundown.

The danger of pesticides to worker honey bees during their lifetime (M. Sanford). Click image to enlarge.

Commercial beekeepers transport:

Commercial beekeepers transport (“migrate”) their colonies during the year to provide pollination services to farmers. Hives may be moved over 1,000’s of miles annually. The USDA estimates that 2.9 million bee colonies were rented for pollination by US farmers in 2007. An estimated 1.5 million colonies are needed each year to pollinate California’s almond trees alone. Managed honey bee colonies are placed in or near crops that require pollination. The beekeeper and the farmer develop a contract (See Cooperate and Communicate) and have a mutual interest that the bees are not harmed by the application of pesticides to those crops. When pesticides are needed, several techniques are used to adequately protect the pollinators and control pests of these crops (see Read and Follow the Label and Pesticide Applicator BMP’s).

Typically, colonies are placed in or near these fields for a short time period; ranging from one to eight weeks depending upon the crop pollination requirements. During the remainder of the year, most managed honey bee colonies reside within flight distance of crops which are attractive to bees but do not require pollination by insects such as cotton, corn, soybeans, and many other major crops. Honey bees will visit these crops or areas whenever nectar or pollen is available. It is critical for growers to be aware of the activity of pollinators in these crops and follow the practices outlined in this module to avoid harming them.

**This kind of resource partitioning by bee colonies accounts for the inconsistency observed many times between colonies undergoing pesticide poisoning in the same location. The bees are not all working the same plants and so some are affected more than others. Often it is those bees with established flight patterns located in an area before pesticide is applied that are most damaged. Those placed in a field immediately after application are less affected by the pesticide because it takes some time for the bees to scout an area and locate food sources. From Protecting Honey Bees from Pesticides by Malcolm Sanford, Extension Beekeeping Specialist, Univ. of FL.