Exclusion involves using barriers to prevent wildlife from accessing resources like food, shelter, and water. Exclusion has many advantages. First, it can be used before any damage occurs. When planting trees in an area with a high deer population, protect newly planted trees with fencing to prevent damage. Second, exclusion does not use chemicals that may harm non-target animals or people. Third, exclusion provides immediate, long-term, and often complete protection.

Some exclusion measures or devices may seem too costly, particularly when large areas need protection (Figure 4.1). Before landowners reject exclusion, advise them to consider its long-term benefits. For example, installing a $250 stainless-steel chimney cap to deter raccoons and other wildlife from entering a chimney is a cost-effective measure, considering the expense of their removal. If the cap lasts 20 years, the annual cost will be $12.50. Another common misperception is that exclusion disrupts the beauty of the landscape. Although aesthetic arguments may be overstated, exclusion often can be made less obtrusive. For example, well-maintained wooden fences can enhance a home’s value and be aesthetically attractive. Shrub plantings can be used to conceal fences.

Figure 4.1. Good fences exclude wildlife. Photo by Paul D Curtis.

When Considering Exclusion

Know the animal

Different animals require different approaches to exclusion. For instance, does the species burrow, climb, jump, or fly? Can the animal chew through fence materials? Each of these abilities demands a different kind of exclusion.

Place dry sticks in front of openings to determine whether animals are using them. Photos by Stephen M. Vantassel.

Exercise Caution

You risk entrapping an animal within the excluded area or building whenever exclusion is used. Never secure openings unless you are sure that animals are not using them. When you are uncertain whether animals use an opening, monitor activity by placing dry sticks in front of the opening. If an animal moves through, it pushes the sticks aside (Figure 4.2). You can also use crumpled newspaper to plug the hole. Monitor the hole for at least five consecutive days of fair, warm weather. Some animals, such as woodchucks, hibernate during the winter in cold climates and remain inactive between November and January.

Exclusion for Specific Situations

In addition to selecting exclusion based on the species, the type of exclusion to use depends on what is being protected.

Protecting decks, sheds, and foundation crawl spaces

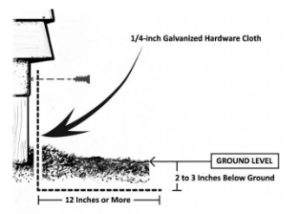

Structures that lack full foundations (e.g., trailers, sheds, and decks) are vulnerable to entry by skunks, raccoons, woodchucks, and other burrowing animals. Trenched wire mesh is used to prevent animal access (Figure 4.3). Increase the depth and skirting of the mesh in locations subject to frost heaving or when dealing with wildlife, such as woodchucks, that dig aggressively. Use ½-inch, galvanized mesh wire if more airflow is needed. Pay special attention to corners to ensure that they are adequately protected. Screens should overlap 4 to 6 inches to prevent any gaps that could be exploited by digging animals. Crushed gravel is not sufficient for these situations.

A trench screen is installed to protect a crawl space. Image by Michael S. Heller.

Protecting individual trees and plants

Use wire or plastic tree guards to protect trees from trunk girdling. More expensive wire guards offer longer-term protection against damage. When using tree tubes to protect plants, place a plastic screen over the top to prevent trapping cavity-nesting birds.

Install a wire or plastic mesh fence around young trees and shrubs to protect them from deer damage (Figure 4.4). Anchor the fence securely to posts, as animals can bend it to reach branches or the trunk. Fences should be 6 feet high to protect individual plants from deer.

Mesh fences protect shrubs from deer. Photo by Paul D Curtis.

For protection from beavers, place wire fences with 1- x 2-inch mesh wire at least 4 inches away from the trunk. Extend the fence 4 feet high and bury the bottom 6 inches into the soil to prevent a beaver from digging under it.

Use nets to protect trees and other fruit-bearing plants from bird depredation. Ensure the nets reach the ground, as birds may try to fly or walk underneath. Poles and wires are often used to support nets for low-growing shrubs, such as blueberries or raspberries.

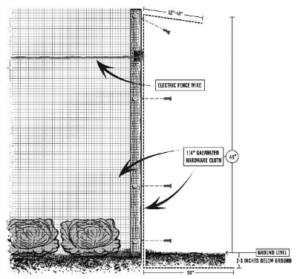

Protecting large areas and gardens from mammals

Fences are the most reliable exclusion technique for preventing mammals from damaging nursery stock, gardens, and home landscapes. Non-electric barriers prevent access to many species and have the added benefit of low maintenance (Figure 4.5). Electric wires can be added outside non-electric barriers to stop climbing animals like raccoons and squirrels.

A wire mesh fence with added electric wires prevents animals from burrowing or climbing into a garden. Image by Michael S. Heller.

Different animals require different fence designs, so we have provided dimensions and types of fences for excluding common species in the following table.

| Species | Fence type | Minimum fence dimensions |

| Deer | Barrier | 8 feet high for large areas; 6 feet high for individual plants. |

| Deer | Electric | There are two strands, 1 foot and 3 feet from the ground for small areas; a 7-wire vertical fence for large areas. |

| Rabbits | Barrier | 1-inch-mesh wire buried 4 inches into the soil and extending 3 feet above the ground |

| Raccoons | Electric-enhanced Barrier | 1-inch mesh buried 2 inches and extended underground 1 foot. The fence should extend 4 feet above ground with an electrified wire 6 to 8 inches from the top. |

| Raccoons | Electric | 2 strands of electric wire, 5 and 10 inches above the ground. |

| Woodchucks | Barrier | 1-inch wire mesh buried 2 inches, extending underground 1 foot. To prevent climbing, the fence should extend 4 feet above ground and have a 1-foot overhang, or an electric wire 6 to 8 inches below the top. |

| Woodchucks | Electric | Two strands of electric wire, 5 and 10 inches above the ground. |

Unfortunately, fences can be expensive, especially when large areas require protection. Barrier fences typically cost significantly more than electric fences due to the high costs associated with materials such as woven wire, posts, anchors, braces, fasteners, and labor. Electric fences use a painful but harmless shock to create a psychological barrier to animals. Frequent monitoring and control of vegetation are required to maintain sufficient shocking power (at least 3,000 volts) on the fence. Electricity can be used exclusively, as with the “poly-tape fence” (Figure 4.6), or in conjunction with a non-electric fence.

A two-strand electric fence can keep deer out of corn. Photo by Unknown.

Fences can be powered through electric outlets, disposable batteries, or rechargeable batteries connected to a solar panel. Modern low-impedance chargers deliver pulses of electricity that deliver a painful, but not continuous, jolt of electricity. The gap in the pulse allows people and animals to move away from the fence. While the shock is generally safe for adults and older children, it could harm young children and people with heart pacemakers. Many chargers can power over 200 miles of fence. Electric fences can protect home gardens from deer and woodchucks during the growing season.

Protecting areas from birds

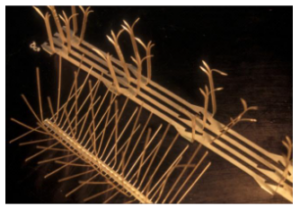

Birds’ mobility makes it difficult to exclude them from sensitive areas. Several techniques are available, however, to help reduce conflicts. Use ledge products (barrier or electric) to prevent birds from roosting or nesting on ledges (Figure 4.7). These devices are easy to install and make it difficult or uncomfortable for birds to perch at treated locations. Install ledge products on surfaces that are out of reach of the public.

Cat Claw® (upper) and Nixalite® spikes (lower) are two of the many models of non-electric ledge products. Photo by unknown source.

Nets prevent birds from accessing buildings, fruit trees, and gardens (Figure 4.8). A mesh size of 2 inches will exclude pigeons or larger birds. Use ¾-inch-mesh netting to exclude smaller birds. Select nets that are resistant to ultraviolet rays. Before winter, remove nets suspended horizontally or secure them with additional support to withstand the weight of snow or freezing rain.

Nets may be installed to prevent birds from accessing sensitive areas or trees—photo by unknown source.

Protecting bird feeders

Many gardeners enjoy birds and maintain feeders to encourage birds to visit their yards. Unfortunately, unwanted animals, such as skunks, raccoons, rats, mice, and squirrels, may also be drawn to the feeder. Several tactics protect bird feeders. First, place bird feeders on poles at least 10 feet away from ledges or tree branches where squirrels can jump. Install baffles on the pole to prevent animals from climbing. Finally, reduce the spilled seed that can reach the ground by installing catch basins (Figure 4.9).

This properly installed bird feeder features a baffle and pan to collect fallen seed—photo by Stephen M. Vantassel.

Protecting window wells

Many people are unaware that wildlife can become trapped in window wells that are 4 inches deep or more. Covering window wells can help prevent this and the potential for a smelly experience when a skunk falls in (Figure 4.10).

Window well cover. Photo by Stephen M. Vantassel

Protecting chimneys

Some birds and mammals, such as swallows, wood ducks, squirrels, and raccoons, view chimneys as ideal nesting sites. They can enter living spaces through open dampers or build nests on closed ones, posing fire risks. Use approved chimney covers to prevent this (Figure 4.11).

Example of a commercial chimney cap. Attach the cap to the flue so that raccoons cannot remove it—image by Homesaver Pro.

Supplies

This module highlighted only a sample of the products available to exclude wildlife. We encourage readers to obtain product catalogs from wildlife control supply companies. Members of trade associations, such as the National Wildlife Control Operators Association, continually test new products and serve as a valuable source of information.