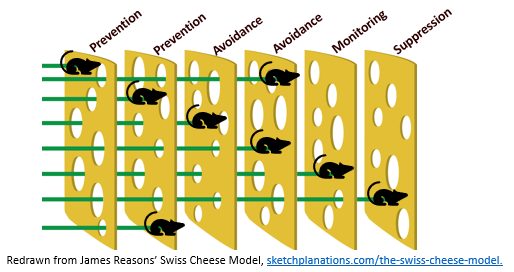

Successful wildlife damage management relies on the knowledge and use of multiple tools or actions. The acronym, PAMS, which stands for Prevention, Avoidance, Monitoring and Suppression, is an easy way to remember the actions you can take in integrated wildlife damage management.

The “Swiss cheese” model below depicts a PAMS approach for mouse control. (Note: you may use different tactics, so don’t view this as standard practice.) The first two slices represent prevention tactics such as: 1.) sealing holes or cracks (¼ in. or larger) to exclude mice from buildings, or 2.) installing brush-type door sweeps that block the gap between the threshold and door base. The two avoidance slices focus on making an area unattractive for mice; Examples include: 1) not allowing trash to accumulate directly outside the building, or 2) moving trash bins further away from entrances. Regularly monitor areas mice are known to infest, such as kitchens and pantries, for signs of their presence (e.g., fecal pellets, seed, and insect carcasses). Commercial pest managers may use non-toxic detection bait blocks or detect signs of gnawing on cardboard boxes. Snap traps, a common suppression tool, may be used for monitoring as well–catching one mouse may indicate that there are more. If further action is needed, suppression tactics such as an adequate number and arrangement of traps (e.g., twelve traps for 2-3 mice is not too many) should be used.

Use the entire PAMS approach as a tool to prevent or reduce conflicts caused by wildlife, rather than relying solely on trapping or elimination. Depending on the situation, preventative and avoidance measures may be sufficient. Success from the use of any one tactic, or single PAMS category of tactics, is never guaranteed, but their integration helps ensure the best results. Actions that should be considered within each PAMS category are described below.

First, know your wildlife!

WCOs or homeowners must correctly identify common wildlife species and the associated damage they may cause, including an awareness of the types of wildlife that may be potential pests in an area. Once you have identified the species, you must determine if the species is regulated, protected, or unprotected (see Laws Concerning Wildlife Damage). In addition, knowing the target species will reveal important biological features such as feeding habits, behaviors, and population dynamics (e.g., biological and cultural carrying capacity).

Prevention

- Habitat management and sanitation. Remove food, water, or shelter that attracts animals or reduces the biological carrying capacity and, thus, the number of animals in an area. For example, if someone has conflicts with rats, the clean-up and removal of available food likely will reduce numbers. You could aggressively trap to reduce the population. Still, rats probably will reproduce faster than your trapping efforts can control them, especially when plenty of food and shelter are available.

- Exclude or prevent animals from accessing locations like decks, soffits, vent pipes, or garden and crop areas. Exclusion techniques include closing entry holes in buildings, installing bird nets over fruit trees and berry bushes, and constructing deer-proof fences around orchards or gardens. Exclusion often provides the best long-term control of wildlife conflicts.

Avoidance

- Repel animals from the area using methods that frighten or frustrate (harass) wildlife by using sound, visual displays, smell, and repellents that are sticky or noxious. Several repellents and frightening devices are available, depending on the problem. However, many of these products have not been tested adequately under research conditions and may fail to prevent damage. Most repellents provide short-term control of wildlife conflicts.

- Diversion is the process of luring animals away from protected sites, usually with a food attractant. Although this may sound good in theory, few practical applications exist. First, you need to find a food source that is more attractive than what the animal is currently using. Also, increasing food availability may increase population levels, adding to the property’s potential damage. The effectiveness of diversion often is questionable and almost always short-term.

Monitoring

-

Site visits may reveal access points or non-target animal risks. Use an animal movement indicator to ensure that the resident animal(s) are no longer using the structure or burrow. Movement indicators can be crumpled newspaper wedged in the opening, criss-crossed duct tape, or sticks across the hole. Monitor the burrow entrance and your movement indicators for a minimum of three days of good weather before securing the burrow permanently. Bat watches around a structure at dusk can help you determine entry points and animal numbers. Use game cameras for monitoring bats or birds using openings in a building. Use flour as a tracking powder to identify areas with rodent activity. (Note: flour if left for weeks will attract insects).

Suppression

-

The goal is to solve a specific problem, not remove all the animals in an area. People should accept the difference between a raccoon living in an attic and a raccoon walking through the backyard.

-

Reduce the number of animals by control methods such as trapping, shooting or the use of toxicants (if legal). Such actions typically lead to a rapid decrease in the population to a level in which they, or their associated damage, can be tolerated or eliminated. Lethal control alone, however, often fails to reduce long-term damage. If suitable habitat and food resources remain available, populations will rebound, sometimes very quickly. Well-fed animals often have larger litters and greater success in raising young to maturity. Population reduction sometimes fails because new animals move into a vacant area. For example, the WCO may have successfully removed voles from one property at a given time. However, the landowner did not understand that other voles would quickly move in from neighboring properties, and soon occupy the habitat previously used by the voles you removed. Some pest problems (such as those with highly mobile animals like deer or Canada geese) need to be managed by multiple property owners to provide a lasting solution to the problem.

-

Specialized methods (e.g., fertility control, biological controls, guard animals, raptors, etc.). Owl boxes are used in Idaho to reduce meadow vole populations (Utilizing Barn Owl Boxes for Management of Vole Populations, University of Idaho). Guard dogs may be used to protect livestock from coyotes. Egg oiling will reduce reproduction of Canada geese but you will need the appropriate federal and state permits to implement this technique.

|

|

| Barn owl in hay pile. Photo by Jason Thomas, Univ. of Idaho Extension Educator |

Barn owl box in field. Photo by Jason Thomas, Univ. of Idaho Extension Educator |

-

Use safe methods: Just because a technique or method works does not mean it should be used. For example, mixing strychnine with cat food or putting out a bowl of radiator antifreeze may effectively kill opossums and raccoons. These techniques, however, are irresponsible and illegal. Poisoning non-target animals results in unnecessary suffering. Use only the most appropriate, practical, legal, and species-specific methods for resolving the problem.

-

Use humane and ethical methods: WCOs need to do their job humanely, ethically, and as discreetly, as possible. People want to control damage from animals, not kill and hurt animals by neglect and inhumane dispatch methods. Resolve conflicts and only remove offending animals if necessary.

-

Follow all local, state, and federal laws: Most states have strict wildlife laws and regulations (See Laws Concerning Wildlife Management). If there are no permitting requirements for WCOs, there are still hunting and trapping laws. The landowner must have a valid nuisance complaint for WCOs to take wildlife. WCOs also must follow government laws and regulations. Suppose a client requests something beyond what you know to be legal, ethical, or safe. In that case, you should suggest more reasonable alternatives or consider declining the job.

- Use cost-effective methods: It may not be practical to manage an offending animal if the expense of resolving a problem is more than the cost of the problem itself. On the other hand, a $250 stainless-steel chimney cap may seem expensive, but when a client understands that the chimney cap will protect a home from animal entry for decades, the cost may be reasonable. If the cap lasts 20 years, the annual cost of the cap is just $12.50. Thus, a chimney cap provides a long-term, inexpensive, and permanent solution, and provides clients with a tested method for excluding wildlife from chimneys.

The information on this webpage is based on the contents of the Wildlife Control Operator Core Training Manual published by the National Wildlife Control Training Program.