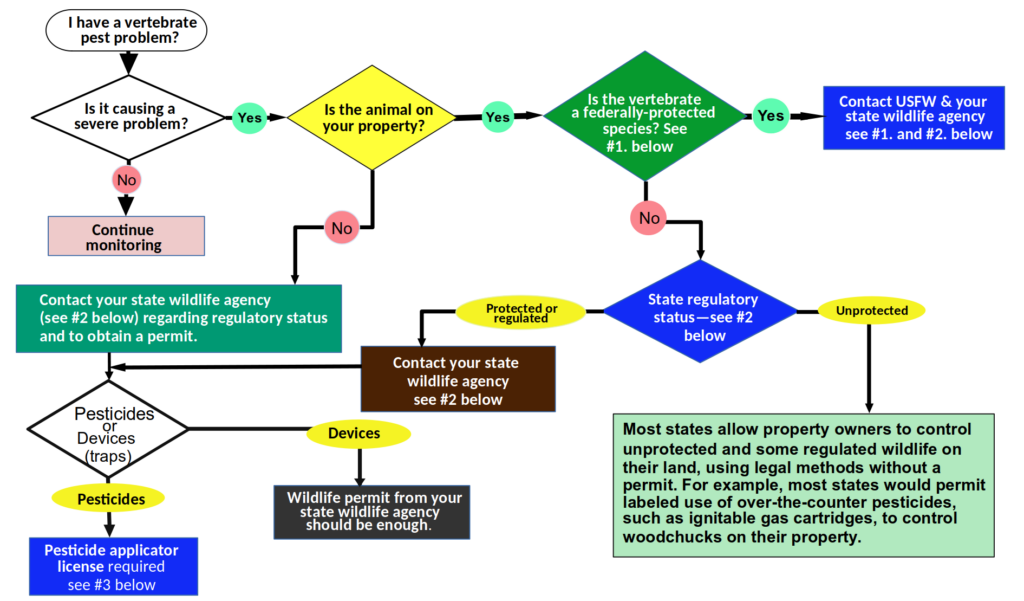

Federal, state, and local laws and regulations must be adhered to when managing, controlling, and capturing wildlife. Protected status, open seasons, legal capture methods, and disposition are all influenced by federal laws and state hunting and trapping regulations. Migratory birds are protected by federal law and cannot be taken without species-specific permits. Management of marine mammals or other marine organisms may also require special permits or licensing through the state wildlife agency or the federal marine fisheries agency. Animal removal, transport, and disposition may also require professional certification. The use of regulated toxicants almost always requires a separate pesticide applicator license. Wildlife causing damage may be controlled outside of typical hunting and trapping seasons. Depending on the species, the WCO may require special permits, which are typically issued to the landowner. Use the flowchart below for guidance in determining the need for permits, licenses, or other authorizations for wildlife management.

Flowchart links:

#1. U.S. Fish and Wildlife Services ePermits: Do I Need a Permit?

#2. State and Territorial Fish and Wildlife Officers [wildlifeforall.us]

#3. Pesticide Applicator License Control Officials

Federal Agencies and Laws

Four major federal agencies regulate work related to wildlife. The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS) protects and manages threatened and endangered species, as well as migratory birds. The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) regulates the use of pesticides. The Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) governs worker safety rules. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) also provides recommendations for preventing human and other zoonotic diseases. The following provides brief descriptions of pertinent federal laws and regulations.

The Migratory Bird Treaty Act (MBTA) protects all migratory birds and their feathers, nests, and eggs. It does not include pigeons, house sparrows, European starlings, or Eurasian collared-doves, as they are not native species to the area. You must have a federal permit to take (kill), possess, or transport migratory birds, nests, or eggs. The law does not require a permit to rescue a raptor trapped in a building, provided the bird is not harmed and is released outdoors immediately.

Before you attempt to control a migratory bird (e.g., woodpeckers, raptors, and waterfowl), the landowner must obtain a 50 CFR Depredation Permit from the USFWS (USFWS Bird Depredation Permit). The permit allows the taking of migratory birds that have become a nuisance, are destructive to public or private property, or pose a threat to public health or welfare. The permit outlines the conditions under which birds may be controlled and the methods that may be employed. Permit holders may control migratory birds that are causing, or are about to cause, serious damage to crops, nursery stocks, or fish in hatcheries. A fee is required for the permit. Federal and state permits are required for the control of resident goose eggs in nests. However, in many states, the process has been simplified to online registration: https://www.fws.gov/eRCGR/. Egg control techniques for Canada geese require a multi-year commitment. All eggs laid by a goose in its lifetime (possibly 40–50 eggs or more) must be treated to equal removing one adult female.

A federal depredation permit, or state authorization, is not needed to simply harass or scare birds (except eagles and federally-listed threatened or endangered species). Some states have USFWS General Depredation Permits for managing resident Canada geese, so individual permits are not needed.

State and local ordinances may further define control activities. For example, in New York State, the Environmental Conservation Law states, “Red-winged blackbirds, common grackles, and cowbirds destroying any crop may be killed during the months of June, July, August, September, and October by the owner of the crop or property on which it is growing or by any person in his employ.” Local laws may limit the types of treatments (e.g., pyrotechnics or firearms) that can be used for managing birds. Check local and state laws before attempting to manage any bird species.

The Federal Insecticide, Fungicide, and Rodenticide Act (FIFRA) regulates the availability and use of pesticides. A pesticide is any substance or mixture of substances intended for preventing, destroying, repelling, or mitigating any pest. The term “toxicant” is used in wildlife pest management to refer to a pesticide used to kill or impair a pest. Repellents deter animal activity while not causing permanent harm or injury and are classified as pesticides. Other pesticides include rodenticides (used for rodent control), avicides (used for bird control), and fumigants, a type of pesticide active as a gas.

The EPA classifies some pesticides as restricted-use pesticides (RUPs). RUPs are available for use only by certified or licensed pesticide applicators. Those not classified as RUPs are considered general use pesticides (GUPs) and may be purchased over the counter. Many GUPs contain the same active ingredients as those found in RUPs. The difference is that GUPs present less risk to people and the environment. They generally have lower concentrations of the active ingredient, are sold only in small quantities (1 pound or less), or are labeled for lower-risk uses. In many states, anyone using pesticides (whether a RUP or GUP) in a commercial application must be a certified pesticide applicator, which requires completing coursework, passing an examination, and obtaining state licensure.

Pesticide labels contain information that helps reduce the risk of harm to people or the environment. The label is the law – using a pesticide contrary to the label is illegal and punishable under federal and state laws.

State Agencies and Laws

The major agencies involved in wildlife-related work at the state level include: (1) Wildlife and natural resources agencies, (2) Departments of Agriculture, (3) Pesticide Review Boards, and (4) State Departments of Health and Human Services. Generally, state laws impose additional restrictions on federal laws and regulations. They cannot be less restrictive. Certain wildlife species, including migratory birds, eagles, and marine mammals, are protected by both state and federal laws and regulations. States typically classify wildlife in the following ways:

1. Game species that may be legally hunted and typically taken for meat. A state hunting license is required to capture or “take” a game animal (e.g., white-tailed deer, turkeys, waterfowl, rabbits, squirrels, etc.).

2. Furbearer species are captured for fur, usually through trapping. A state hunting or trapping license is required to capture or “take” a furbearer (e.g., raccoons, gray and red foxes, beavers, muskrats, coyotes, etc.).

3. Non-game species are not harvested, and no open seasons are available. Most non-game wildlife species are protected and cannot be harmed. (e.g., songbirds, reptiles, amphibians, etc. ).

4. Unprotected wildlife includes some non-native nuisance species (e.g., European starlings, Asian carp, Norway rats, or house mice) that have no restrictions on their take (killing). Typically, licenses or permits are not required to shoot, fish, or trap these species. These species can be taken at any time in any manner as long as other state and local laws are followed (e.g., discharge distances for firearms).

Local Agencies and Laws

The major local agencies involved in wildlife-related work include: (1) municipal animal control officers, (2) Humane societies, (3) County sheriff and police departments, and (4) County Departments of Health and Human Services. In recent years, animal control agencies have attempted to apply humane regulations regarding the treatment of domesticated animals to the treatment of problem wildlife. For example, people have been cited for animal cruelty because cage-trapped animals did not have access to water. Animal protection groups argue that state laws protecting animals against cruelty also apply to wildlife. Therefore, WDM activities must be discreet and adhere to the highest standards of professionalism. Just because a technique is legal does not mean it is wise or appropriate. Always consider how others might perceive a conflict situation.

Non-target Animals

Generally, a non-target animal is an individual or species that is incidentally captured or taken. If the animal is classified as a species you can manage, then most states allow you to deal with it as the landowner wishes. If the species is a rabies vector (e.g., raccoon, skunk, fox, or coyote), some states require euthanization or limit transport distances. The legal situation becomes more unclear when the non-target is a domestic animal, as these are typically under the jurisdiction of animal control officers (ACOs) and are also considered private property. House cats frequently enter cage traps. If the cat is owned, it must be released. However, it is often unclear if feral cats are legally classified as wild or domestic. Most states do not clarify the legal status of feral cats. Therefore, it is recommended to work with local animal shelters when capturing feral domestic animals. Your local government may require domestic species to be taken to your local animal shelter for final disposition. Always understand the laws and regulations before you act.

Portions of text on this webpage are based on the contents of the Wildlife Control Operator Core Training Manual published by the National Wildlife Control Training Program.